Kane, Harnett T. pp. 238-248. William Morrow and Co. NY 1945.

[…]

In the meantime the rival John Andrews had been at work. Looking around the countryside soon after his arrival, he had met on an adjoining plantation the Virginia-born Penelope Lynch Adams, descendant of the family for whom Lynchburg was named. During the early years of their marriage a traveling artist passed, and the couple had their portraits made. His shows a clear-skinned countenance, cool eyes, and firm chin, linen frill held with pearl pin. Penelope is softly graceful, slim-throated above her velvet and chiffon, at her throat a camellia from her garden. She gave her husband no sons, but five daughters were born in quick succession. Taking a glance at the similar production rate of girls at the nearby Randolphs’, the neighbors said there must be something in the air here.

This stretch of Virginia on the Mississippi was not well looked on by its Creole neighbors. Paul Octave Hebert, highly influential among the people of the coast, was supposed to have been particularly unimpressed by these interlopers. Prejudice grew so strong that for a time the new families feared they might have to leave. To the surprise of the natives, Andrews and his father-in-law, old Kit (Christopher) Adams, set our to storm the citadel of Creolism: Hebert himself. No less good-humored than wily, the Virginians threw themselves headlong at the barriers and broke through. The Creoles, perhaps to their own annoyance, found themselves liking the new arrivals. Peace ensued, with an amusing consequence that we shall shortly see.

The French neighbors now called and fondled the five little Andrews. Politely they observed that, after all, girls were nice; and who was to question the will of le bon Dieu? And also, Monsieur and Madame Andrews, they were still young. The Creoles knew of cases. … Had they heard of Valcour Aime, who had to wait for the fifth time to get his Gabi? But the good wishes were not realized. When she was thirty-two, the fragile Penelope gave up the burden of looking after her daughters. Grandmothers and aunts and cousins lent their hands; remaining unmarried, the father devoted his free hours to the girls.

Times were improving rapidly; the year 1856 brought Andrews the more than pleasing cash return of $97,000. By this time he, too, was thinking of a background for his adolescent maidens. In New Orleans he sought our Gallier and his son, designers of Ashland and other river places. But by the standards of the late 1850s these earlier establishments seemed a trifle ingenuous. What Andrews would get was a place stamped with a certain power, yet different from most of the others that bore the Gallier name, and without a parallel on the river. Slowly the framework materialized for an imposing central structure and two wings, certainly the heaviest thing that anyone here had beheld. Many shrugged. That house wasn’t going to be finished. There weren’t enough bricks or wood anywhere for that! Steamboats dumped crates of carved work and iron, so large that oxen had to be brought to the riverfront to haul them. Toward the end Andrews asked his daughters to stay away from the site until all was complete. One afternoon he summoned them. With beating hearts they leaned forward as the carriage drew near. The vehicle reached a curve in the road; the girls stared in silence, as others were to stare during the years to come.

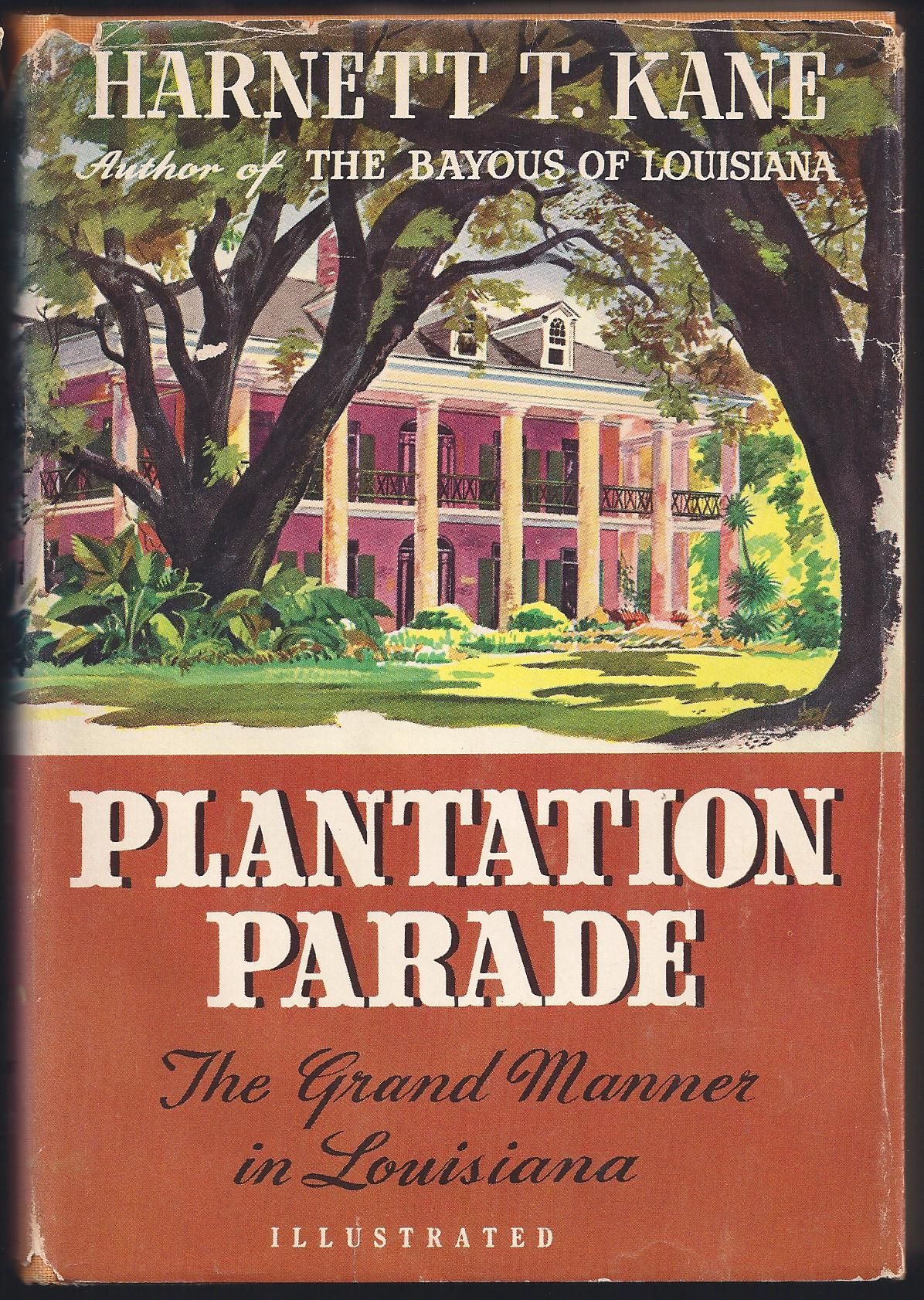

It was grandeur in pink, an off-shade that was almost a purple. Suggesting the strength of a heavy fortification, it raised itself two stories into the air, with a cavernous attic, the whole heavy mass above a twelve-foot basement. Riding about it, the observer felt that he was looking at four or five separate structures. The great bulk of the front façade had four florid Corinthian columns, dwarfing any others in this region. The richly carved capitals alone stood six feet tall, of solid blocks of cypress. Behind each pillar rested a pilaster with similarly lavish topping, and the columns supported a pediment of the enormous width and height that the proportions of the house demanded.

Along the deep portico a narrow inner gallery was upheld by powerful scrolled brackets with cast-iron work for ornamentation. (Such inner galleries were among the many non-Louisiana touches. The climate called for greater ventilation than they usually provided.) From the porch, a flight of marble steps sloped downward; heavy blocks of covered brick on each side. At the right, a large extension of the house ended in a second portico. Except for the pediment and the stairway, this extension was a duplicate of the main part, with ponderous pillars, inner gallery, and the rest. At the opposite exposure, not far from the central façade, jutted a rounded wing like half of a medieval tower.

Beyond the ornate doorway spread the vast middle hall, marked by elaborate columns and pilasters, lesser versions of the exterior ones, with arches and double arches, more friezes and scrolls and brackets. At the back it widened toward a winding stairway, one of the most celebrated parts of the celebrated whole. Following the curve of the stairs, the outside wall was rounded; at the second-floor level a stained-glass window suffused the passages with rectangles of colored light. Everywhere opened side passages, bedrooms, dressing-rooms, and closets; a rear wing held the housekeeper’s and servants’ quarters.

The tower-like section near the main portico turned out to be an extension of the drawing-room. Draperies were in place, so that the oval chamber thus created was partly private. As time went by, it was known as the “flirtation room,” a point fraught with dangers to the unattached male. The room, too, held what became a storied “courting sofa.” Seated upon it, the natives declared, at least eleven swains had succumbed to the appeal of eleven Louisiana belles. After that, the coast people lost count.

A final check of rooms gave a total of seventy-five, against fifty for the Randolphs. If the Randolphs showed hand-painted doorknobs, the Andrews had theirs of silver, complete to keyhole guards. Before the residence stood an imposing line of oaks and pecans. A landscape gardener was improving it and laying out twenty-eight acres of shrubs and flowers. The land had formerly belonged to old Mr. Bell, and was called Bell Grove. In these more effusive days the title was altered to read Belle Grove.

John Andrews and his daughters basked in it. They laughed when, as often happened, some guests got lost in the intricate windings. A wrong turn, and the stranger found himself hopelessly isolated. Along the coast, tall tales multiplied of the way the family used to discover the limp frames of visitors who had been unable to make their way back before collapsing with hunger and exhaustion. A few did not smile; those Andrews, they informed their friends, couldn’t last long with a place like that. They were courting trouble.

The Andrews were also courting life, and with gusto. Although they could not know it, a race was on between their own magnificence and the war that would wither it. The girls flourished in new silks; the crops continued high. Belle Grove saw its first wedding. At the Opéra in New Orleans, Emily met Monsieur Edouard Schiff, a financier of Paris. (“A true Frenchman,” in the words of one of the present-day families, “slim, blond, goateed,” and, they thought, “inclined to be supercilious.”) He visited Belle Grove, and invitations went out for what is recalled as the most ornate pre-War entertainment on the coast.

A week in advance came an imposing retinue, Imbert, chef and caterer extraordinary from New Orleans, with wife, family, and working corps. The skill of the group was approached only by its temperament. Imbert took over the kitchens, opening his supplies of eggs, his chocolates, his truffles, and his wines, shunting aside any who got in his way. His stall sniffed, tasted, rejected. Imbert strolled about, taking in everything, clapping hands in reproof, slapping an assistant’s face to make his disapproval emphatic. The night before the wedding, the family was summoned to see what he had achieved.

A room was spread with dishes the size of platters, with daubes glacés, the tender meat in a quivering jelly thick with spices and mushrooms; then oyster concoctions of five or six varieties, in liquids light and dark, concealed under this and that. Side tables offered objects that were neither cakes nor pies, but something zestfully between. Metal containers held juices green or brown or creamy, soups, bouillons, punches, and, in a place of separate display, the salads, those meals in themselves, of fish and meat, for which Imbert was particularly known. In the middle of it all rose his specialty of nougats, this time in the shape of steamboats and palaces and swans, and, towering toward the chandeliers, a pink replica of Belle Grove itself. The family cried out its pleasure; Imbert permitted himself a thin smile.

The next day, fifty house guests moved in with maids and valets, to stay a week. About five hundred others arrived by steamboat or carriage, or were rowed across the river by their slaves. By evening the porticos were strung with lights by the thousand, shining across the river in the dusk. Along the hallways, on the piazza, about the stairs, canvas had been laid for dancing; flowers garlanded mantels, stairs, and porches. The bride and her father marched down the curving staircase, along the wide hall. In the alcove, the sometime “flirtation room,” waited the minister. Entertainments followed, to the accompaniment of champagne and toasts. On the levee outside, the uninvited watched the crush of carriages, the people moving in the gardens, and Belle Grove itself in a new guise, its pink beauty enhanced under the twinkling of the artificial lights.

Like his neighbor Randolph, Andrews went to Texas during the War. Afterward, Belle Grove lifted its head with something of its old air. The daughters were engaged; eventually the last one was disposed of. Penelope married, ironically, young Paul Hébert, son of the erstwhile hater of Andrews and other Virginians. The father had seemed at the point of forcing the new family off the Mississippi; the boy merged the fortunes of the Héberts and the Andrews. The experiment might have been termed a success; the younger Hébert was elected Governor of Louisiana.

Yet within a decade of its construction, by 1867, John Andrews had to give up his Belle Grove. Hadn’t they said so? demanded the disapproving. Nobody could keep it up for long-that, that pink elephant! From New Orleans appeared a commission merchant, Henry Ware, to put down $5o,ooo in cash. The retiring John Andrews took practically all his furniture to New Orleans and deposited it in a warehouse. Shortly afterward, the storage place burned down. For a time Belle Grove was empty; then a son, James A. Ware, took it. The father had wanted him to be a lawyer, but sugar had drawn him. He married the daughter of another coast planter, Mary Eliza Stone of Glencoe, and Belle Grove witnessed a second and greater period of splurge.

Mary Eliza Ware brought to the pink palace not only her beauty, but also the taste and inheritance of an heiress. Traveling in Europe and America, she sent boatloads of material back to Louisiana: paintings, tapestries, escritoires, foot stands, armoires, wall-pieces-an interior splendor to fit the florid walls. And Belle Grove had a hostess with an air to equal its potentialities. She is pictured as a social woman, whose joy was the soirée, the assembling of eighty-five people at a table, the planning of a week-end party for sixty couples, with a tournament a la Walter Scott. The river folk invariably recall her as attired in evening clothes: black velvets, décolleté, with trains, and ropes of jewels and a diamond lorgnette. With her dashing looks went a head of fiery red hair, which never faded. She kept her figure, her air, and her scarlet tresses.

“When she entered a room, the rest of the women suddenly looked plain.” “She reminded you of a Duchess, or what a Duchess is supposed to be like.” When friends tried to talk of plantation business, she lifted her hand; such things were fatiguing. Did they mind? … And she rustled away, followed, as was her custom at some of her fêtes, by two grinning Negro boys in Oriental costume, turbans and all. Several of the river people tell of an incident. Mrs. Ware dropped a diamond earring at the dinner table; two men leaned over to hunt for it. “Don’t bother, please,” she smiled. “The servants will probably sweep it up in the morning.”

The union of Stones and Wares produced an heir apparent, Stone Ware. As a boy at Belle Grove, he proceeded to do what story-book children so often do; he got lost. “For about five minutes,” he told me, “I pattered about, and then I did a sensible thing. I screamed like the devil until they came for me.” As the only son and only grandson, he concedes that he was “a spoiled brat, hardly fit to live with. I had, I guess, anything a kid could ask, except maybe companionship. I eventually learned to get along without that. The people who got off the steamboats to walk around Belle Grove used to watch me, hanging around like a little Lonesome Luke. Some envied me, they say; I suppose I would have, too, if I’d been in their shoes. Anyhow, I had very little to worry about. Maybe that was something.”

As a boy Stone Ware climbed the turret of the oval room and used a telescope to survey the countryside like a ship’s captain, he accompanied his mother on visits of state in a carriage that was all shiny black and immovable glass. He perspired in the heat and choked on the smell of camphor balls, but the visits had to be made; his mother was much attached to him and liked to show him about the coast. He could watch the great parties if he did it quietly. He recalls the nights he leaned over the curving stair to see the people, the men always in black, the women in whites or pinks and wearing flowers. He went to sleep to the tinkle of laughter from the galleries below. One other memory comes back to him. On an upstairs wall hung an oil portrait that had been there when the Wares arrived. He never knew who it was; somehow he absorbed the idea that the man was watching over the house as its guardian. Now and then, the Negroes told him, the man left the frame and walked about Belle Grove.

Stone Ware was well taught-private tutors, military school in Virginia, several years at Tulane, and the Audubon Technical School to find out about scientific sugar. Back home, he was allowed to slip into the sugar manufacture and gradually to take over the management. During his off hours he was the gilded young man of the coast-a debonair, well-set-up boy with engaging light-blue eyes. He confesses he “never knew a place with so many beauties as this one.” Another, less privileged in those days, pictures him: “Somebody clattered along the road, on a handsome horse, a fellow with all the composure in the world. He drew up sharp before the bar, tossed the reins to a Negro, and strode in. He took several drinks, and he was affable, yes, and nodded to several people. But he drank alone. After he rode off, I was told he was Stone Ware, just back from college. Lord, how I resented him!”

His father had put up a race track; Stone Ware added a second one. The Wares seldom did anything in a small way. Stone organized the Louisiana Trotting Horse Breeders’ Association and traveled with his entries, taking prizes as he went. He was the first man thereabouts with an automobile, a glamorous speedster in tan dust-jacket, goggles, and heavy gloves, and he brought to Belle Grove a state meeting of the racers. Eventually when others had a single car, he owned three-a Peerless, a Chandler, and a red Buick. Through the countryside and through the years moved Stone Ware, surrounded by dozens of people, yet always the Lonesome Luke.

In 1908 James Ware died, the only master of Belle Grove ever to expire within its walls. Stone Ware took over, and for a time there was scant change-the parties, the calls of state, the visits to the races, all went on. Between Stone and his mother there continued a strong affinity. He married a French girl of the parish and they stayed in a smaller house near Belle Grove. Children came quickly; an outsider would have said that Stone Ware had everything in life.

One year a hurricane ripped at his cane; the next, an early freeze split the stalks and turned the juice to vinegar. The economic situation tightened. Sadly, he had to tell his mother, “We can’t make the crop this time.” Such a thing had seldom if ever happened at the old Belle Grove; it could not happen many times, or they would be ruined. Stone Ware tried diversification, subdivisions, new manufacturing schemes. Nothing worked; and, as he talked of this, Stone Ware grew grave. “It was as if a curse had been put on the place. Sugar is the biggest gamble on earth, but it wouldn’t pay off for me at the end. I needed just one thing-time; and I couldn’t get enough of it.”

In 1924 a line of vehicles headed for Belle Grove, For once they were not going there for a party. Antique dealers appraised the sets of rosewood and mahogany, the sofa from the “flirtation room,” and the hundreds of other pieces. Extra trucks, heavy floats, were called for; days were needed to clean out the treasure that Eliza Stone Ware had collected. When Stone Ware glanced about the bare walls he saw something that everyone had overlooked-the portrait of the unknown man, the “guardian” of Belle Grove. He had preceded them there, and he had outlasted them.

Stone Ware lives today in a small apartment on Bienville Street in New Orleans. A stout, white-haired man in white shirt and seersucker trousers, he showed little bitterness when we met. He served lemonade with all the éclat of a man providing a julep in the older era. No, he had not seen the plantation house since that day; he did not want to. He is not regretful about his life. “I’ve acquired experience if not virtue. You know, I think I may even have done some good, by accident, here and there.”

Even if the plantation itself had continued in operation, the great house had been marked down for ruin many years ago. He had watched the river encroach upon Belle Grove. When he first went there, the Mississippi was a half-mile or more away; then it had moved in, a few hundred yards at a time. Yet might not the structure be saved, even now? He did not seem interested. “Maybe it would be the proper way for it to go, that way. … If they would only let the river take it one day, pillars and everything.” Quietly Stone Ware, brought up to champagne in a palace, sipped his lemonade.

Each time that I have visited Belle Grove in recent years, the sight has come as a shock. In this air, decay advances at least as rapidly as growth; and man has done his part to prod apart this carcass of what had been a handsome thing. On my last trip I found the paneled doors and windows ripped out, the last few hanging by broken hinges. All the ironwork had been pulled off. Sections of wooden scrolls, having collapsed, lay half-hidden in the weeds. In one place gaped a hole in the wall through which a team could be driven; a force of men, wanting bricks, had come with a wagon and torn them from the base. The whole right wing collapsed a few years back; that side presented the silhouette of a despoiled cathedral. Wild vines climbed along the pillars that Eliza Stone Ware’s servants had kept scrupulously bare. Against the sky, out of the delicate lines of the chimney, grass was growing.

The pink coating of the walls faded slowly in the sun and damp air, with streaks of wet discoloration down the sides. Cracks widened in the masonry; masses of the walls were slipping off. The house lay open to every breeze, and, as I walked about it during a fall afternoon, the winds whistled dismally. The gallery flooring had collapsed; only by inching across a beam was it possible to get inside. There the wreckage was worse. Once-fine interior columns, still firmly in place, had tarnished. Exposed to rain and wind, the carved friezes had rotted into gray fragments. The last stairway had fallen away, and the walls dripped. Even on this dry, chilly day, a pool of stagnant water still stood in one room, a thin scum on its surface. Near the door I fingered the stringy remnant of a cord that had once brought a servant scurrying. All of these servitors were now in their graves. The place itself was a corpse of the old Belle Grove.

Of the thousands of acres, seventeen were left. Much of the sweeping line of trees and shrubs had likewise vanished. As the river ate closer, these growths were taken; some were killed by lightning, and vandals entered and chopped at others. Stumps stood alone in the yard, and the house was the more gaunt as it soared out of the sere earth. But the fortress-like basement and those two sets of towering Corinthian columns seemed to be rooted for eternity, like ruins of another Athens.

As I drove past a spot a few miles away, the rival house Nottoway glowed in its whiteness, under the last rays of the sun. From the road its high, slim shafts were unmarred, its ironwork giving a finished perfection to the endless lines of balconies, the whole settling within a border of great trees. A row of crepe myrtles thrust their cotton-like blossoms against a railing. The long shutters were being closed against the air of the early night. In a rocker a man was sleeping, a newspaper on the floor beside him.

Nottoway had been more fortunate than the other house. Though it shifted from hand to hand, it ended in the possession of Dr. W. G. Owen, who had once attended the Wares. Dr. Owen, growing up in the vicinity, had gazed long and often on Nottoway, hoping that he might own something like it. One day he found it within his reach, and he has maintained it in something of its former state. The duel of the masters has had an unexpected ending. Belle Grove’s builder succeeded in the early stages. The man who erected Nottoway has achieved the final victory.

To read more stories like this and view pictures of the lost home, join the Belle Grove Discussion Group.

To purchase a copy of this book, click here.